UAE: Saud Bin Saqr – A Sheikh like no other?

Saud Bin Saqr Al Qasimi was born in 1956 as the fourth son of Sheikh Saqr Bin Muhammad Al Qasimi of Ras Al Khaimah. Back then, Britain still controlled the Arab sheikhdoms of the Persian Gulf, and oil had not yet made Abu Dhabi rich. Saud was born at the Al Maktoum Hospital in more advanced Dubai where commerce with Iran and India flourished. At the time, Ras Al Khaimah had no hospital and little trade. In fact, Ras Al Khaimah had been infamous for piracy in the Persian Gulf. Like Dubai, it had a natural harbor. But the inlet at Ras Al Khaimah had mostly sheltered Arab pirate ships until the British authorities in Bombay dispatched a fleet that defeated the Qasimi and their tribesmen at the battle of Ras Al Khaimah in 1819, forcing them by treaty a year later to renounce plunder and piracy forever.

In 1971 Britain ended its protectorate over the so-called Trucial States and gave way to the creation of the UAE led by Abu Dhabi and Dubai. The following year, Ras Al Khaimah joined the federation. Shortly afterwards, the 17 year old Saud was sent to study economics at the American University in Beirut in summer 1973. But the start of the Lebanese civil war in 1975 prompted his transfer to the University of Michigan in the United States where he obtained a bachelor’s degree. After four years in America, Saud returned to Ras Al Khaimah in 1979 and was appointed Head of his father’s Emiri Court. He then headed the Municipal Council in1986.

But Saud’s first transformational experience came with Khater Massaad. The Swiss-Lebanese geologist had just finished a study on water in the neighboring sheikhdom of Fujairah when Saud invited him to Ras Al Khaimah in 1989. In Ras Al Khaimah, Massaad suggested that he could use local raw materials to produce tiles. Massaad devised the concept of RAK Ceramics. Established in 1991, the factory in Ras Al Khaimah developed from the scratch into the world’s biggest producer of tiles over a period of only 20 years. It was and is still good business for Saud, who personally holds almost 40 percent of the company. In comparison, the Government of Ras Al Khaimah barely benefits from RAK Ceramics. Its share is less than five percent, although it was the government that had provided land, infrastructure, and financial support.

The second happy moment came in 2003. Saud’s elder half-brother Sheikh Khalid Bin Saqr had been Crown Prince and Deputy Ruler for decades. With their father ailing, the infighting for succession started. As in other Arab dynasties, there was and is no clear primogeniture rule. Changes, including those made last-minute by incumbent rulers, can never be excluded. Nobody knows exactly what happened behind the scenes in Ras Al Khaimah when in June 2003 Sheikh Khalid was removed as Crown Prince and replaced by the younger Saud. Khalid, it was reported, promoted women’s rights and a more open society. His wife was a very vocal activist among women in Ras Al Khaimah. Khalid advocated a tough line against Iran whose Tunb Islands in the Persian Gulf are claimed by Ras Al Khaimah. Khalid led street protests against the invasion of Iraq in 2003. All this would have irritated the UAE leadership in Abu Dhabi. A meeting of the two frail sheikhs, Zayed of Abu Dhabi and Saqr of Ras Al Khaimah, would have sealed Khalid’s fate.

The result: By 2003, Khater Massaad had made Saud a rich man. At the same time, family intrigue had catapulted Saud to power. As new Crown Prince, Saud became the de facto ruler of Ras Al Khaimah. But his position was by no means safe. The old Sheikh Saqr was still alive and could change his ailing mind. Khalid continued campaigning against Saud. From 2003 until their father’s death in 2010 both Saud and Khalid positioned themselves for succession.

For Saud, the strategy was clear. He needed more financial firepower to underpin his claim to Ras Al Khaimah. In this poor emirate, it is money and favors that create and maintain loyalties among the local tribesmen. What Saud had to do was creating a mechanism to raise funds. His personal income from RAK Ceramics and a few other ventures in Ras Al Khaimah was not enough. The federal subsidies from Abu Dhabi were something Saud could not control. New sources were needed. In 2005, he got his ailing father’s approval on the establishment of the Ras Al Khaimah Investment Authority (RAKIA). But this investment authority was different from its namesakes in Kuwait, Abu Dhabi, or Qatar. Instead of having assets in the billions backed by oil and gas, RAKIA with its misleading name actually started borrowing money.

Some of the money went into Ras Al Khaimah, with a bit of real estate here and some construction there. Massaad and Saud brought World Bank expertise into Ras Al Khaimah, promoting the concept of living and investing there. Tourism real estate projects were developed. Finally, mimicking the big successful cousins in Dubai, Saud created the Ras Al Khaimah Free Trade Zone (RAK FTZ). Its aim was and is to attract foreign investments to the emirate at prices more competitive than the ones charged in Dubai. But although a few genuine investors have come, most companies registered at RAK FTZ have remained just names. Playing on their quasi-sovereign status as individual sheikhdoms within the UAE enables sheikhs of the poorer emirates to grant legal status to companies, even if these companies are only letterboxes. For most investors, a mere registration certificate from the RAK FTZ is all they want to be able to conduct their real business elsewhere. Even the chronic electric power shortage of Ras Al Khaimah that hinders development is therefore no problem for such investors. And collecting fees for issuing registration documents is already enough for Saud.

Other and larger funds went abroad, in particular to Georgia, a pivotal country in the Caucasus between Turkey, Russia, and Iran as the key regional players. RAKIA bought the Sheraton Metechi Hotel in 2007 for 68 million US dollars and Poti Sea Port for 145 million US dollars in 2008. Real estate projects were supposed to be developed by Rakeen Development, a separate company owned in half privately by Saud’s family. Rakeen bought land in Tabakhkmela. The rakeen.com website still advertises a fancy project there on paper. But with the exception of Tbilisi Mall (where the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation is shareholder), nothing new was created. Instead, Saud unexpectedly decided in October 2010 to sell all assets in Georgia.

What was the reason for the timing?

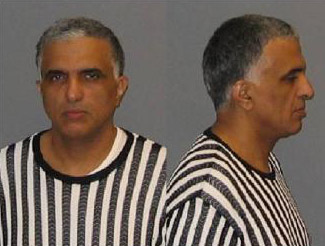

The sheikh and crown prince connection helped elsewhere, too. In June 2005, Saud was arrested for criminal sexual conduct in the 3rd and 4th degree. While staying at the upscale Broadway Plaza in in Rochester in the US State of Minnesota, he sexually assaulted a housekeeper. When the police came to his penthouse, Saud claimed diplomatic immunity. But the County Attorney’s Office in Rochester ordered him to be arrested. When the Department of State in Washington D.C. confirmed that Saud Al Qasimi did not have diplomatic immunity, Saud was kept in jail over the weekend until the following Monday. In the end, one of the investigators involved in the case said they believed “Sheikh Saud’s status as a head of state played a role in charges not being pursued.” In line with principles of rule of law in the US, the ten pages of detailed investigation and testimonies are documented by the Rochester Police Department (see http://www.thesmokinggun.com/documents/crime/sheikhs-dirty-secret

Accumulating enormous debts, parking large amounts of money abroad, and embarrassing personal conduct have started eroding Saud’s authority in Ras Al Khaimah. The majority of the around 100,000 national population of the emirate have difficulties finding their place in society. The trendy marketing language employed to attract companies to register at RAK FTZ or tourists to Hamra Fort Resort does hardly appeal to locals. The talk of Ras Al Khaimah “emerging as a destination” or “transitioning to a knowledge-based economy“ may temporarily work for outside consumption. Neither in leadership positions nor at the workers’ level in Ras Al Khaimah’s industry are enough opportunities for local Emiratis. Internally, critics have been on the rise.

It is not by chance that the UAE-wide Reform and Social Guidance Association (also known as “Islah”) has strong support in the poorer northern emirates. And it is not the socially marginalized but the politically aware who are demanding government transparency and accountability. One of their leaders, Dr Muhammad Al-Mansuri, a human rights lawyer from Ras Al Khaimah, was Saud’s legal advisor until 2009. He was fired for criticizing the limitations on freedom of expression. Islah was the movement bringing the Arab Spring to the UAE. As a result, the authorities across the UAE cracked down on dissent over the past two years. As recently as July 2013, the Federal Supreme Court in Abu Dhabi sentenced 56 activists, among them Mansuri and the prominent human rights lawyer Dr Muhammad Al-Rukn, to ten years in prison. Eight others were sentenced in absentia to fifteen years; and five defendants were sentenced to seven years. “Unfair trial, unjust sentences,” is how Amnesty International summarized the process. “The conviction of 69 government critics is a low point for the UAE’s worsening human rights record and its serious abuse of due process rights,” said Joe Stork, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “These unfair verdicts and the UAE’s efforts to shut down criticism should be a wakeup call to UAE’s international allies.”

William K. Grant is a retired Royal Navy officer and consultant on Middle Eastern affairs

Comments are closed.